The New Republic has practiced a confrontational, sometimes combative, style of criticism since its early issues—its clarion call Rebecca West’s essay on “The Duty of Harsh Criticism.” Our reviewers tend to be more interested in vigorous discussion of a book and its ideas than in handing out gold stars. This end-of-year “best of” list reflects those tendencies. This far from exhaustive list features 10 books that fueled surprising and worthwhile conversations—and sparked a few disputes.

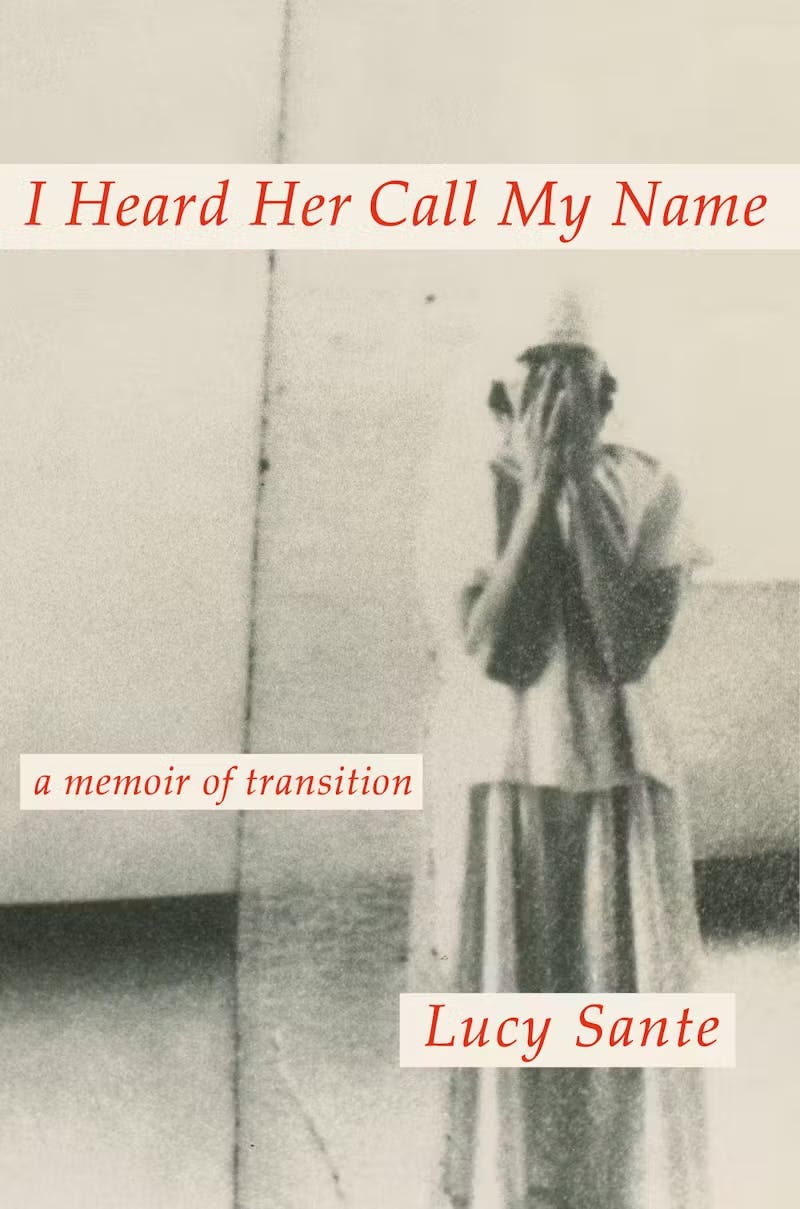

I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition by Lucy Sante

Penguin Press, 240 pp., $27.00

“Playfulness, imaginative force, and ferocious close reading” have long characterized Lucy Sante’s writing, from her subterranean history of New York, Low Life, to her explorations of The Other Paris. Yet, despite publishing a memoir in 1999, she had left corners of herself deliberately unexplored. Her memoir of transition, I Heard Her Call My Name, attempts to fill in those silences, using the techniques of examination and reexamination that make her work so rich and revealing. “Alongside Sante’s experiences navigating the new social and emotional territory that comes with acknowledging her gender,” Lidija Haas writes in her review, “I Heard Her Call My Name explores other kinds of transition, and transitional objects—it’s about taste, in art and music and crushes and books and clothes, and the ways it can build and sustain or obscure a self.”

Read our full review.

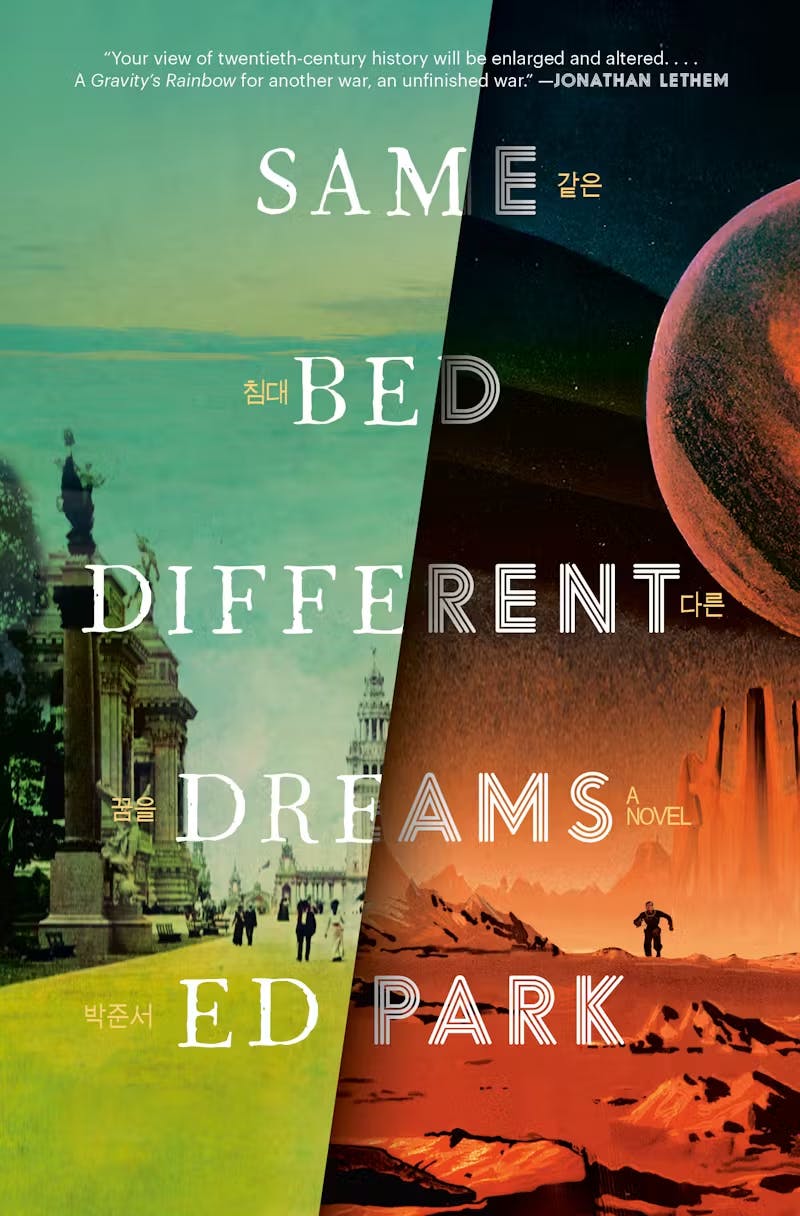

Same Bed Different Dreams by Ed Park

Random House, 544 pp., $30.00

Same Bed Different Dreams takes its title from “a popular saying in Korea, which invokes the way two people in a marriage or a family might share a life but have very different aims for that life—a perfect metaphor, it turns out, for the differences and similarities in Korean diasporic identities,” Alexander Chee writes. As the novel moves between North Korea in 1952 and literary New York in the present, Park builds “an alternate history of Korea and its relationship to the United States in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, telling a story by mining and transforming the historical record. And it begins with a question that returns again and again, until it is almost like a chant in a protest: What is history?”

Read our full review.

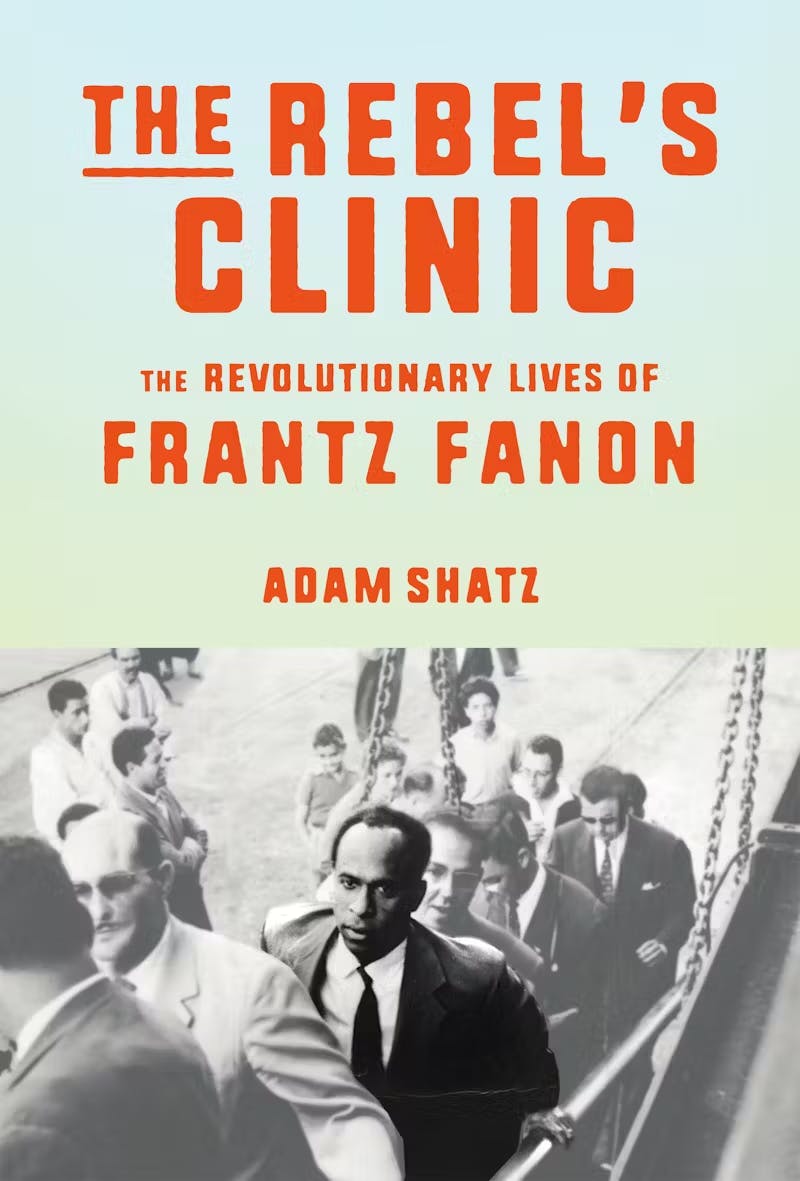

The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon by Adam Shatz

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 464 pp., $32.00

“Unlike many of the thinkers read by insurgents half a century ago, Frantz Fanon remains hugely influential today,” Eric Herschthal writes. “When radicals (and would-be radicals) issue calls for ‘decolonization,’ they are invoking Fanon’s vision of liberation through the dismantling of privileged enclaves. One reason for his continuing appeal is that he can be read in so many different ways: as a proponent of political violence and a chronicler of its destructiveness; as a spokesman for Black identity and a critic of its limitations; as a visionary of postcolonial utopia and a Cassandra of postcolonial failure.” An engrossing narrative, Adam Shatz’s new biography, The Rebel’s Clinic, “deserves to be the first stop for anyone looking for an introduction to Fanon’s life and work.”

Read our full review.

James by Percival Everett

Doubleday, 320 pp., $28.00

Does Percival Everett write “philosophical novels, or are they novels with philosophy in them? Don’t expect an easy answer,” Gene Seymour warns, “because such questions, whether raised by the author or the reader, are part of the point—and the fun—of Everett’s fiction.” Everett’s new novel James is a “reimagining of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the point of view of Jim, the Black slave with whom Twain’s eponymous young hero runs away from their Missouri home via raft along the Mississippi River.” In Everett’s version, Jim is playing a trick on Huck throughout the novel, bending language to his own purposes and creating his own series of games.

Read our full review.

Homeland: The War on Terror in American Life by Richard Beck

Crown Publishing Group, 592 pp., $33.00

Beck’s enthralling survey of the recent past shows how 9/11 continues to shape our present and has left us with what he calls an “impunity culture”—a government-wide inability to face consequences or change tack. As Ed Burmila writes, the subsequent “interventions” in Iraq and Afghanistan revealed “a fragile superpower more desperate to maintain appearances than to make rational investments.” The invasion of Iraq was as bloodthirsty as it was illogical; through Beck’s eyes, we examine the nauseating security theater of the years following the attacks and the legacy of such decisions today: “a world in which we rationalize which rights (usually those of other people) we are willing to trade for the illusion of greater security.”

Read our full review.

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner

Scribner, 416 pp., $29.99

Rachel Kushner’s novel about “Sadie Smith,” a spy-for-hire in the south of France, is a shrewd and thrilling commentary on gender dynamics: Kushner’s spy recognizes how easily young women are dismissed or underestimated, and finds it is to her advantage when she infiltrates a group of radical eco-activists and no one asks too many questions about who she is or what she is doing. In order to understand her subject, Sadie has to immerse herself in their wide-ranging discussions of partisans, rebellions, handfishing, caves, activist strategy, and the nature of humanity itself. “As in a Graham Greene or John le Carré novel,” Laura Marsh writes, “in Creation Lake the point of spying is to find out not just what is happening but how to pick one’s way through a world of ideas.”

Read our full review.

Colored Television: A Novel by Danzy Senna

Riverhead Books, 288 pp., $29.00

For Danzy Senna, “identity politics is as much a playground as a battleground,” Stephen Kearse writes in his review of Colored Television. “Building on her long-running interest in television as both a pastime and a trick mirror, the book is set in present-day Los Angeles, where novelist Jane Gibson wants to break into screenwriting.” Her new career path takes her into the status-obsessed world of “prestige” TV, where “representation” is a buzzword rather than a serious commitment.

Read our full review.

When the Clock Broke: Con Men, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked Up in the Early 1990s by John Ganz

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 432 pp., $30.00

“How did Trump, a figure of faint ridicule in the closing decades of the last century, become the defining figure of the American right in the opening decades of this one? For historian John Ganz, it’s impossible to answer these questions without understanding the early 1990s—an era when the smug meliorism of the Reagan years broke down, the kooks and cranks of American political life came in from the fringes, and a feral spirit of paranoia and rage threatened to take up permanent residence in the body politic,” Aaron Timms writes in his review of Ganz’s When the Clock Broke. Ganz’s thesis is that the right-wing radicals of the ’90s set the stage for 2016: “David Duke, paleoconservative Pat Buchanan, shock jock Rush Limbaugh, New Right pamphleteer Sam Francis, election bomber Ross Perot, and mob boss John Gotti: These men walked so Donald Trump could run.”

Read our full review.

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates

One World, 256 pp., $30.00

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s The Message is a thought-provoking collection of three interwoven essays that blend memoir with a guide to good writing. Exploring themes of nationalism, oppression, and belonging, Coates reflects on his journeys to Dakar, Senegal; Columbia, South Carolina; and Palestine. He examines the power of storytelling alongside issues including slavery, book banning, and Israeli apartheid. The longest section focuses on Palestine, where he confronts the clash between nationalist narratives and lived realities. Addressing young writers, Coates urges them to write in service of a “larger emancipatory mandate,” offering insights into the role of storytelling and mythmaking in shaping our understanding of the world.

Read our full review.

Left Adrift: What Happened to Liberal Politics by Timothy Shenk

Columbia Global Reports, 264 pp., $18.00

How did Democrats lose the votes of the working class? While Republicans once stood for business and Democrats for labor, the last 30 years have “been marked by Democratic helplessness and indifference as the party morphed into a home for the wealthy and highly educated, while the right loomed in the background, slowly making inroads among working-class voters Democrats once called their base,” Ben Metzner writes in his review of Timothy Shenk’s Left Adrift. Instead of focusing on political candidates, Shenk tells the story of political consultants Stan Greenberg and Douglas Schoen, who helped craft center-left party strategies in the United States as well as the United Kingdom, Israel, and South Africa. Greenberg and Schoen brought with them “dueling ideas on how to reverse the losses wrought by dealignment. And through their rivalry, Shenk contends, we can understand the real story of dealignment, and how we might reverse it.”

Read our full review.